Does Wheat Cause Coronary Heart Disease?

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of deaths worldwide - killing 7 millions people every year. In the following text, we will see that wheat consumption is probably a risk factor for CHD.

Conventional Wisdom on Wheat

Most health organizations currently view wheat as a safe food except for people having celiac disease - affecting up to 1% of the population - and people having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Also whole wheat - as part of whole grains - is considered to be one of the healthiest foods. In fact a diet rich in whole grains is considered to be protective against CHD.

Why? Because observational studies consistently find that whole grain consumption is associated with a decreased risk of CHD. Do these results contradict wheat consumption causing CHD?

Are Whole Grains Protective Against CHD?

According to this study:

Whole grain intake consistently has been associated with improved cardiovascular disease outcomes, but also with healthy lifestyles, in large observational studies. Intervention studies that assess the effects of whole grains on biomarkers for CHD have mixed results.

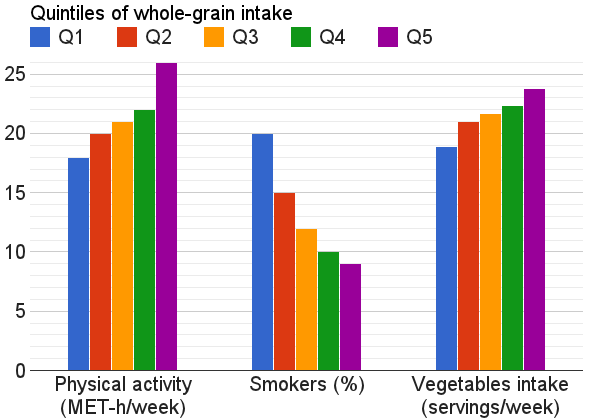

Indeed many studies show that whole grain consumption is associated with a decreased risk of CHD. But these studies are observational and can only show correlation but not causation.

In fact there is an health-conscious population bias in these studies: for example people consuming the most whole grains also exercise more and smoke less:

Of course researchers adjust the data for these risk factors. But it is very difficult, maybe impossible, to adjust for all risk factors. For example the two previously cited studies did not adjust for important risk factors like socioeconomic status or social support.

A classic example of an occurrence of this bias can be found in hormone replacement therapy (HRT): observational studies had found that HRT was decreasing the risk of heart disease risk while a controlled study finally found that HRT was indeed slightly increasing the risk of heart disease.

A proof that this health-conscious bias could explain the seemingly protective effect of whole grains can be found in randomized controlled studies: many of them fail to find any beneficial effect of whole grains compared to refined grains.

So according to these randomized controlled studies whole grains are neutral toward CHD risks. How then can we say that wheat causes CHD?

Are All Grains Created Equal?

Many randomized controlled studies compared wheat with other grains. These trials are usually quite short. So instead of looking at the number of heart attacks, short-term studies focus on risk predictors of CHD like weight gain or markers of inflammation. Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) level is another risk factor. It represents the number of LDL particles - often called “bad cholesterol”. It is now considered to be a better predictor than LDL-C - the amount of cholesterol contained in LDL particles. The lower the level of ApoB the lower is the risk of CHD.

Here are some results of these studies:

- a study concluded that a bread diet may promote fat synthesis/accumulation compared with a rice diet

- wheat increased BMI compared to flaxseed in a 12 months study

- wheat increased ApoB level by 5.4% compared to flaxseed in a 3 weeks study

- wheat increased ApoB level by 7.5% compared to flaxseed in a 3 months study

- wheat increased ApoB level by 0.05 g/L compared to flaxseed in a 12 months study

- oat decreased ApoB level by 13.7% while wheat had no significant effect in a 21 days study

- wheat increased the number of LDL particles by 14% while oat decreased them by 5% in a 12 weeks study

- ApoA to ApoB ratio (a risk predictor similar in efficiency to ApoB alone - here the higher the better) was increased by 4.7% for oat bran and 3.9% for rice bran compared to wheat bran in a 4 weeks study

These studies show that some grains like oat improve the risk factors of CHD compared to wheat. In addition, these studies often show an absolute improvement of the CHD risk profile in groups eating oat and an absolute deterioration in groups eating wheat. Although we cannot say for sure, it would suggest that oat is protective against CHD - which is confirmed by other studies - while wheat increase the risk of CHD.

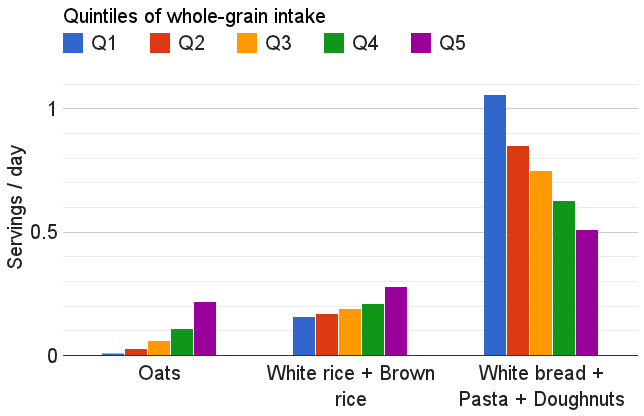

That could help explain why people eating more whole grains are healthier in observational studies since it looks like that they eat more grains like rice and oat and less typically wheat-made food like white bread, pasta and doughnuts:

Now let’s have a look at studies linking wheat and CHD.

Observational Studies on Wheat

Some observational studies linked wheat and waist circumference gains - waist circumference being a strong predictor of CHD:

- a study showed a correlation between consumption of white bread and waist circumference gains

- a study concluded that: “reducing white bread, but not whole-grain bread consumption, within a Mediterranean-style food pattern setting is associated with lower gains in weight and abdominal fat”

- a Chinese study found that “vegetable-rich food pattern was associated with higher risk of obesity” but as noted by obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet the association between obesity is in fact stronger with wheat flour than with vegetables

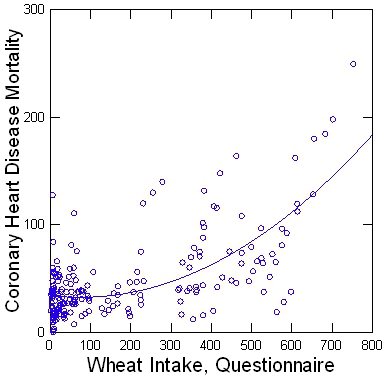

A more pertinent result is found in the data of a large observational study in China. Researchers analysed these data and found a 0.67 correlation between wheat flour intake and CHD. They also found a 0.58 correlation between wheat intake and BMI.

From Denise Minger

From Denise Minger

But this is just a single unadjusted correlation and does not prove much. However author Denise Minger thoroughly analysed the data of this study and found that the association held strongly after multivariate analysis with any other variable available like latitude, BMI, smoking habits, fish consumption, etc.

Since it is an observational study it cannot prove anything but it is yet more evidence suggesting that wheat consumption causes CHD. Let’s now have a look at randomized controlled trials.

Randomized Controlled Trials on Wheat

In addition to the previous randomized controlled trials comparing wheat with other grains there are two additional studies suggesting that wheat consumption causes CHD.

The first one is a study involving rabbits. While studies involving animals are not always relevant to humans - especially studies with herbivore animals like rabbit - the results of this study are quite interesting.

The researchers fed rabbits an atherogenesis diet (i.e. promoting formation of fatty masses in arterial walls) with a supplement of cottonseed oil, hydrogenated cottonseed oil, wheat germ or sucrose. And as they concluded:

Severity of atherosclerosis after 5 months was greatest on the wheat germ-supplemented diet, whereas there were no differences among the other three groups.

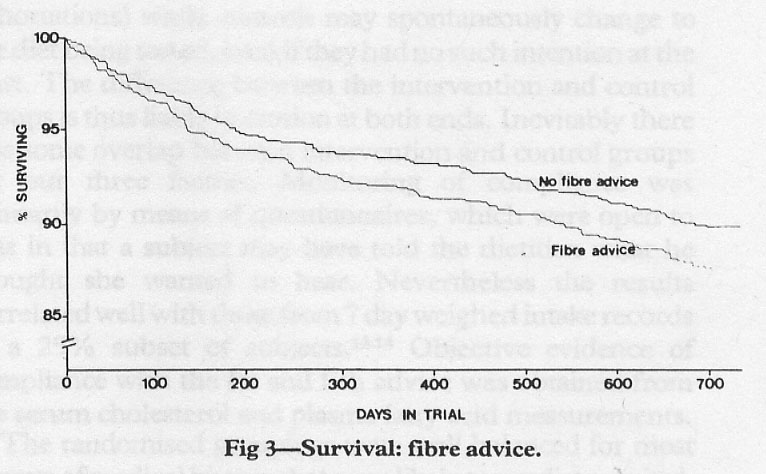

The second study is the Diet And Reinfarction Trial (DART). In this 2-year randomized controlled trial, people who already had recovered from a heart attack were split into groups receiving various advice. The main result of this study was that the group advised to eat fatty fish had a reduction in mortality from CHD.

One other piece of advice - the fibre advice - was:

to eat at least six slices of wholemeal bread per day, or an equivalent amount of cereal fibre from a mixture of wholemeal bread, high-fibre breakfast cereals and wheat bran

Seeing this advice we can guess that most of cereal fibres intake by this group was from wheat although we cannot be sure.

This advice resulted on a 22% death increase:

However this result bordered on statistical significance: the 95% confidence interval being 0.99–1.65.

For people not familiar with statistics, a result is usually defined as statistically significant when there is less than 5% chance that the result is due to luck alone. Here there is a 95% probability that the relative risk is between 0.99 (1% decreased chance of dying) and 1.67 (67% increased chance of dying).

Since the probability that the fibre advice resulted in a protective or neutral effect was a little too high, this result has been quite overlooked. Had the study lasted a little longer, it would have raised way more suspicion toward whole grains.

A decade later, in a follow-up study researchers sent self-completion questionnaires to the survivors. This study is less interesting since it had many limitations:

There are a number of limitations to the dietary data collected in this survey. The dietary advice stopped after 2 y and all the surviving men received a letter encouraging them to eat more fatty fish and it is possible that this resulted in immediate dietary changes. The dietary data presented here were collected from at least 85% of survivors some years after the end of the 2 y of dietary advice when around half of the original participants had died. Diet was assessed with a limited number of questions that focused on fish and fibre intake. Questionnaire data were not collected on other aspects of current diet and objective biological measures of fish intake were not obtained. It is thus possible that we were unable to detect important differences in diet.

However, in this study the researchers reanalyzed the original data from the DART study and adjusted for pre-existing conditions and medication use. This time they found the fibre advice to be statistically significant: as we can see in the table 4 they found a hazard ratio of 1.35 (95% CI 1.02, 1.80) for the 2-year period of the randomized controlled trial.

These results are quite telling: according to these researchers, a 2 year randomized controlled trial showed that advising people recovering from a heart attack to eat at least six slices of wholemeal bread per day resulted in a statistically significant 35% percent chance increase of CHD compared to people not receiving this advice.

Wheat, Vitamin D Deficiency And Heart Disease

Many studies found that vitamin D deficiency is associated with CHD.

However vitamin D deficiency does not seem to cause heart disease. For example several studies found that vitamin D supplementation did not prevent heart disease.

As this study concludes:

A lower vitamin D status was possibly associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease. As a whole, trials showed no statistically significant effect of vitamin D supplementation on cardiometabolic outcomes.

Wheat consumption causing CHD could help explaining these results. A study found that wheat consumption depletes vitamin D reserves. That could explain why vitamin D deficiency is associated with heart disease and why it does not seem to cause it: both vitamin D deficiency and heart disease could be consequences of wheat consumption.

Of course this is not the only explanation. For example the DART study shows that fish consumption prevents CHD and fish is a food rich in vitamin D.

Not the Perfect Culprit

To be clear, if it seems likely that wheat consumption is a risk factor of CHD it is not the only one nor the primary one. There are many other factors like smoking, hypertension, lack of exercise or stress. Even among dietary factors wheat is probably not the main one. For example the DART study shows that the protective effect of fish intake is stronger than the adverse effect of wheat.

In addition, deleterious wheat effects might not affect everybody. One study showed that the ApoB level variation following wheat and oat bran intake was different depending on the genotype of the individuals. In another study whole-wheat intake worsened the lipid profile only in people having a specific genotype compared to refined wheat.

How the wheat is cooked may have a role too. Studies show that sourdough bread improves mineral bioavailability (such as magnesium, iron, and zinc) compared to yeast bread or uncooked whole-wheat. Also content in proteins with potential adverse consequences like gluten or wheat germ agglutinin differs depending of the food type.

Conclusion

There is strong evidences that wheat consumption is a risk factor for CHD. People at risk of CHD should avoid wheat as should those trying to lose weight. In all cases, stopping wheat consumption for a month for example to see how one feels without wheat is always a good idea since there is currently no available method to diagnose non-celiac wheat sensitivities and that even for celiac disease, the average delay in diagnosis has been found to be around 10 years in the US, in Spain or in Sweden.

More studies looking at the links between wheat and CHD are urgently needed since CHD is the leading cause of deaths while wheat is the second most widely consumed food and whole-wheat is often advised to lower risk of CHD. Studies considering grains as a whole are bound to give inconsistent results since different grains seem to have opposite effects in the case of CHD. So as much as possible future studies should treat grains separately and consider things like type of wheat products and genetic variability.

Data from

Data from  Data from

Data from